“Self Help; With Illustrations of Conduct and Perseverance”

by Samuel Smiles

This book contains references to the Strutt family, Richard Arkwright and the inventors of the machinery that sparked off Britain's Industrial Revolution. “Self Help; With Illustrations of Conduct and Perseverance” by Samuel Smiles was scanned and proofed by David Price, email ccx074@coventry.ac.uk

CHAPTER II. - LEADERS OF INDUSTRY - INVENTORS AND PRODUCERS

"The worth of a State, in the long run,

is the worth of the individuals composing it." - J. S. Mill.

One of the most strongly-marked features of the English people is their spirit of industry, standing out prominent and distinct in their past history, and as strikingly characteristic of them now as at any former period. It is this spirit, displayed by the commons of England, which has laid the foundations and built up the industrial greatness of the empire.

This vigorous growth of the nation has been mainly the result of the free energy of individuals, and it has been contingent upon the number of hands and minds from time to time actively employed within it, whether as cultivators of the soil, producers of articles of utility, contrivers of tools and machines, writers of books, or creators of works of art. And while this spirit of active industry has been the vital principle of the nation, it has also been its saving and remedial one, counteracting from time to time the effects of errors in our laws and imperfections in our constitution.

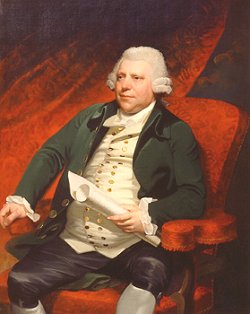

Richard Arkwright, like most of our great mechanicians, sprang from the ranks. He was born in Preston in 1732. His parents were very poor, and he was the youngest of thirteen children. He was never at school: the only education he received he gave to himself; and to the last he was only able to write with difficulty.

in 1732. His parents were very poor, and he was the youngest of thirteen children. He was never at school: the only education he received he gave to himself; and to the last he was only able to write with difficulty.

When a boy, he was apprenticed to a barber, and after learning the business, he set up for himself in Bolton, where he occupied an underground cellar, over which he put up the sign, “Come to the subterraneous barber - he shaves for a penny. “ The other barbers found their customers leaving them, and reduced their prices to his standard, when Arkwright, determined to push his trade, announced his determination to give “A clean shave for a halfpenny. “

After a few years he quitted his cellar, and became an itinerant dealer in hair. At that time wigs were worn, and wig-making formed an important branch of the barbering business. Arkwright went about buying hair for the wigs. He was accustomed to attend the hiring fairs throughout Lancashire resorted to by young women, for the purpose of securing their long tresses; and it is said that in negotiations of this sort he was very successful.

He also dealt in a chemical hair dye, which he used adroitly, and thereby secured a considerable trade. But he does not seem, notwithstanding his pushing character, to have done more than earn a bare living.

The fashion of wig-wearing having undergone a change, distress fell upon the wig-makers; and Arkwright, being of a mechanical turn, was consequently induced to turn machine inventor or “conjurer, “ as the pursuit was then popularly termed.

Spinning Machine

Many attempts were made about that time to invent a spinning-machine, and our barber determined to launch his little bark on the sea of invention with the rest. Like other self-taught men of the same bias, he had already been devoting his spare time to the invention of a perpetual-motion machine; and from that the transition to a spinning-machine was easy. He followed his experiments so assiduously that he neglected his business, lost the little money he had saved, and was reduced to great poverty.

His wife - for he had by this time married - was impatient at what she conceived to be a wanton waste of time and money, and in a moment of sudden wrath she seized upon and destroyed his models, hoping thus to remove the cause of the family privations. Arkwright was a stubborn and enthusiastic man, and he was provoked beyond measure by this conduct of his wife, from whom he immediately separated.

Kay the Clockmaker

In travelling about the country, Arkwright had become acquainted with a person named Kay, a clockmaker at Warrington, who assisted him in constructing some of the parts of his perpetual-motion machinery. It is supposed that he was informed by Kay of the principle of spinning by rollers; but it is also said that the idea was first suggested to him by accidentally observing a red-hot piece of iron become elongated by passing between iron rollers.

However this may be, the idea at once took firm possession of his mind, and he proceeded to devise the process by which it was to be accomplished, Kay being able to tell him nothing on this point. Arkwright now abandoned his business of hair collecting, and devoted himself to the perfecting of his machine, a model of which, constructed by Kay under his directions, he set up in the parlour of the Free Grammar School at Preston.

Being a burgess of the town, he voted at the contested election at which General Burgoyne was returned; but such was his poverty, and such the tattered state of his dress, that a number of persons subscribed a sum sufficient to have him put in a state fit to appear in the poll-room. The exhibition of his machine in a town where so many workpeople lived by the exercise of manual labour proved a dangerous experiment; ominous growlings were heard outside the school-room from time to time, and Arkwright, - remembering the fate of Kay, who was mobbed and compelled to fly from Lancashire because of his invention of the fly-shuttle, and of poor Hargreaves, whose spinning-jenny had been pulled to pieces only a short time before by a Blackburn mob, - wisely determined on packing up his model and removing to a less dangerous locality. He went accordingly to Nottingham, where he applied to some of the local bankers for pecuniary assistance; and the Messrs. Wright consented to advance him a sum of money on condition of sharing in the profits of the invention.

The machine, however, not being perfected so soon as they had anticipated, the bankers recommended Arkwright to apply to Messrs. Strutt and Need, the former of whom was the ingenious inventor and patentee of the stocking-frame. Mr. Strutt at once appreciated the merits of the invention, and a partnership was entered into with Arkwright, whose road to fortune was now clear.

The patent was secured in the name of “Richard Arkwright, of Nottingham, clockmaker, “ and it is a circumstance worthy of note, that it was taken out in 1769, the same year in which Watt secured the patent for his steam-engine.

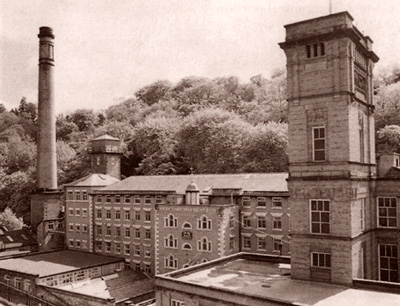

A cotton-mill was first erected at Nottingham, driven by horses; and another was shortly after built, on a much larger scale, at Cromford, in Derbyshire, turned by a water-wheel, from which circumstance the spinning-machine came to be called the water-frame.

Arkwright’s labours, however, were, comparatively speaking, only begun. He had still to perfect all the working details of his machine. It was in his hands the subject of constant modification and improvement, until eventually it was rendered practicable and profitable in an eminent degree. But success was only secured by long and patient labour: for some years, indeed, the speculation was disheartening and unprofitable, swallowing up a very large amount of capital without any result.

When success began to appear more certain, then the Lancashire manufacturers fell upon Arkwright’s patent to pull it in pieces, as the Cornish miners fell upon Boulton and Watt to rob them of the profits of their steam- engine. Arkwright was even denounced as the enemy of the working people; and a mill which he built near Chorley was destroyed by a mob in the presence of a strong force of police and military. The Lancashire men refused to buy his materials, though they were confessedly the best in the market. Then they refused to pay patent-right for the use of his machines, and combined to crush him in the courts of law. To the disgust of right-minded people, Arkwright’s patent was upset.

After the trial, when passing the hotel at which his opponents were staying, one of them said, loud enough to be heard by him, “Well, we’ve done the old shaver at last; “ to which he coolly replied, “Never mind, I’ve a razor left that will shave you all. “

He established new mills in Lancashire, Derbyshire, and at New Lanark, in Scotland. The mills at Cromford also came into his hands at the  expiry of his partnership with Strutt, and the amount and the excellence of his products were such, that in a short time he obtained so complete a control of the trade, that the prices were fixed by him, and he governed the main operations of the other cotton-spinners.

expiry of his partnership with Strutt, and the amount and the excellence of his products were such, that in a short time he obtained so complete a control of the trade, that the prices were fixed by him, and he governed the main operations of the other cotton-spinners.

Arkwright was a man of great force of character, indomitable courage, much worldly shrewdness, with a business faculty almost amounting to genius. At one period his time was engrossed by severe and continuous labour, occasioned by the organising and conducting of his numerous manufactories, sometimes from four in the morning till nine at night.

At fifty years of age he set to work to learn English grammar, and improve himself in writing and orthography. After overcoming every obstacle, he had the satisfaction of reaping the reward of his enterprise. Eighteen years after he had constructed his first machine, he rose to such estimation in Derbyshire that he was appointed High Sheriff of the county, and shortly after George III. conferred upon him the honour of knighthood. Masson Mill, Arkwright's Second Derbyshire Enterprise

He died in 1792. Be it for good or for evil, Arkwright was the founder in England of the modern factory system, a branch of industry which has unquestionably proved a source of immense wealth to individuals and to the nation.

![]() See Arwkright's Family Pedigree HERE

See Arwkright's Family Pedigree HERE

Other Industrialists

All the other great branches of industry in Britain furnish like examples of energetic men of business, the source of much benefit to the neighbourhoods in which they have laboured, and of increased power and wealth to the community at large. Amongst such might be cited the Strutts of Belper; the Tennants of Glasgow; the Marshalls and Gotts of Leeds; the Peels, Ashworths, Birleys, Fieldens, Ashtons, Heywoods, and Ainsworths of South Lancashire, some of whose descendants have since become distinguished in connection with the political history of England.

Among other distinguished founders of industry, the Rev. William Lee, inventor of the Stocking Frame, and John Heathcoat, inventor of the Bobbin-net Machine, are worthy of notice, as men of great mechanical skill and perseverance, through whose labours a vast amount of remunerative employment has been provided for the labouring population of Nottingham and the adjacent districts.

William Lee

The accounts which have been preserved of the circumstances connected with the invention of the Stocking Frame are very confused, and in many respects contradictory, though there is no doubt as to the name of the inventor. This was William Lee, born at Woodborough, a village some seven miles from Nottingham, about the year 1563.

![]() See William Lee's Portrait and Account HERE

See William Lee's Portrait and Account HERE

According to some accounts, he was the heir to a small freehold, while according to others he was a poor scholar, and had to struggle with poverty from his earliest years. He entered as a sizar at Christ College, Cambridge, in May, 1579, and subsequently removed to St. John’s, taking his degree of B.A. in 1582-3. It is believed that he commenced M.A. in 1586; but on this point there appears to be some confusion in the records of the University. The statement usually made that he was expelled for marrying contrary to the statutes, is incorrect, as he was never a Fellow of the University, and therefore could not be prejudiced by taking such a step.

At the time when Lee invented the Stocking Frame he was officiating as curate of Calverton, near Nottingham; and it is alleged by some writers that the invention had its origin in disappointed affection. The curate is said to have fallen deeply in love with a young lady of the village, who failed to reciprocate his affections; and when he visited her, she was accustomed to pay much more attention to the process of knitting stockings and instructing her pupils in the art, than to the addresses of her admirer. This slight is said to have created in his mind such an aversion to knitting by hand, that he formed the determination to invent a machine that should supersede it and render it a gainless employment. For three years he devoted himself to the prosecution of the invention, sacrificing everything to his new idea. At the prospect of success opened before him, he abandoned his curacy, and devoted himself to the art of stocking making by machinery.

This is the version of the story given by Henson on the authority of an old stocking-maker, who died in Collins’s Hospital, Nottingham, aged ninety-two, and was apprenticed in the town during the reign of Queen Anne.

It is also given by Deering and Blackner as the traditional account in the neighbourhood, and it is in some measure borne out by the arms of the London Company of Frame-Work Knitters, which consists of a stocking frame without the wood-work, with a clergyman on one side and a woman on the other as supporters.

Whatever may have been the actual facts as to the origin of the invention of the Stocking Loom, there can be no doubt as to the extraordinary mechanical genius displayed by its inventor. That a clergyman living in a remote village, whose life had for the most part been spent with books, should contrive a machine of such delicate and complicated movements, and at once advance the art of knitting from the tedious process of linking threads in a chain of loops by three skewers in the fingers of a woman, to the beautiful and rapid process of weaving by the stocking frame, was indeed an astonishing achievement, which may be pronounced almost unequalled in the history of mechanical invention.

Lee’s merit was all the greater, as the handicraft arts were then in their infancy, and little attention had as yet been given to the contrivance of machinery for the purposes of manufacture. He was under the necessity of extemporising the parts of his machine as he best could, and adopting various expedients to overcome difficulties as they arose. His tools were imperfect, and his materials imperfect; and he had no skilled workmen to assist him.

Lee's First Attempts

According to tradition, the first frame he made was a twelve gauge, without lead sinkers, and it was almost wholly of wood; the needles being also stuck in bits of wood.

One of Lee’s principal difficulties consisted in the formation of the stitch, for want of needle eyes; but this he eventually overcame by forming eyes to the needles with a three-square file. At length, one difficulty after another was successfully overcome, and after three years’ labour the machine was sufficiently complete to be fit for use. The quondam curate, full of enthusiasm for his art, now began stocking weaving in the village of Calverton, and he continued to work there for several years, instructing his brother James and several of his relations in the practice of the art.

Having brought his frame to a considerable degree of perfection, and being desirous of securing the patronage of Queen Elizabeth, whose partiality for knitted silk stockings was well known, Lee proceeded to London to exhibit the loom before her Majesty.

He first showed it to several members of the court, among others to Sir William (afterwards Lord) Hunsdon, whom he taught to work it with success; and Lee was, through their instrumentality, at length admitted to an interview with the Queen, and worked the machine in her presence. Elizabeth, however, did not give him the encouragement that he had expected; and she is said to have opposed the invention on the ground that it was calculated to deprive a large number of poor people of their employment of hand knitting.

Lee was no more successful in finding other patrons, and considering himself and his invention treated with contempt, he embraced the offer made to him by Sully, the sagacious minister of Henry IV., to proceed to Rouen and instruct the operatives of that town - then one of the most important manufacturing centres of France - in the construction and use of the stocking-frame. Lee accordingly transferred himself and his machines to France, in 1605, taking with him his brother and seven workmen.

He met with a cordial reception at Rouen, and was proceeding with the manufacture of stockings on a large scale - having nine of his frames in full work, - when unhappily ill fortune again overtook him. Henry IV., his protector, on whom he had relied for the rewards, honours, and promised grant of privileges, which had induced Lee to settle in France, was murdered by the fanatic Ravaillac; and the encouragement and protection which had heretofore been extended to him were at once withdrawn.

To press his claims at court, Lee proceeded to Paris; but being a protestant as well as a foreigner, his representations were treated with neglect; and worn out with vexation and grief, this distinguished inventor shortly after died at Paris, in a state of extreme poverty and distress.

Lee’s brother, with seven of the workmen, succeeded in escaping from France with their frames, leaving two behind. On James Lee’s return to Nottinghamshire, he was joined by one Ashton, a miller of Thoroton, who had been instructed in the art of frame-work knitting by the inventor himself before he left England. These two, with the workmen and their frames, began the stocking manufacture at Thoroton, and carried it on with considerable success.

The place was favourably situated for the purpose, as the sheep pastured in the neighbouring district of Sherwood yielded a kind of wool of the longest staple. Ashton is said to have introduced the method of making the frames with lead sinkers, which was a great improvement. The number of looms employed in different parts of England gradually increased; and the machine manufacture of stockings eventually became an important branch of the national industry.

One of the most important modifications in the Stocking-Frame was that which enabled it to be applied to the manufacture of lace on a large scale. In 1777, two workmen, Frost and Holmes, were both engaged in making point-net by means of the modifications they had introduced in the stocking-frame; and in the course of about thirty years, so rapid was the growth of this branch of production that 1500 point-net frames were at work, giving employment to upwards of 15,000 people. Owing, however, to the war, to change of fashion, and to other circumstances, the Nottingham lace manufacture rapidly fell off; and it continued in a decaying state until the invention of the Bobbin-net Machine by John Heathcoat, late M.P. for Tiverton, which had the effect of at once re-establishing the manufacture on solid foundations.

John Heathcoat

John Heathcoat was the youngest son of a respectable small farmer at Duffield, Derbyshire, where he was born in 1783.

When at school he made steady and rapid progress, but was early removed from it to be apprenticed to a frame-smith near Loughborough. The boy soon learnt to handle tools with dexterity, and he acquired a minute knowledge of the parts of which the stocking-frame was composed, as well as of the more intricate warp-machine. At his leisure he studied how to introduce improvements in them, and his friend, Mr. Bazley, M.P., states that as early as the age of sixteen, he conceived the idea of inventing a machine by which lace might be made similar to Buckingham or French lace, then all made by hand.

When at school he made steady and rapid progress, but was early removed from it to be apprenticed to a frame-smith near Loughborough. The boy soon learnt to handle tools with dexterity, and he acquired a minute knowledge of the parts of which the stocking-frame was composed, as well as of the more intricate warp-machine. At his leisure he studied how to introduce improvements in them, and his friend, Mr. Bazley, M.P., states that as early as the age of sixteen, he conceived the idea of inventing a machine by which lace might be made similar to Buckingham or French lace, then all made by hand.

The first practical improvement he succeeded in introducing was in the warp-frame, when, by means of an ingenious apparatus, he succeeded in producing “mitts “ of a lacy appearance, and it was this success which determined him to pursue the study of mechanical lace-making.

The stocking-frame had already, in a modified form, been applied to the manufacture of point-net lace, in which the mesh was LOOPED as in a stocking, but the work was slight and frail, and therefore unsatisfactory. Many ingenious Nottingham mechanics had, during a long succession of years, been labouring at the problem of inventing a machine by which the mesh of threads should be TWISTED round each other on the formation of the net. Some of these men died in poverty, some were driven insane, and all alike failed in the object of their search. The old warp-machine held its ground.

When a little over twenty-one years of age, Heathcoat went to Nottingham, where he readily found employment, for which he soon received the highest remuneration, as a setter-up of hosiery and warp-frames, and was much respected for his talent for invention, general intelligence, and the sound and sober principles that governed his conduct. He also continued to pursue the subject on which his mind had before been occupied, and laboured to compass the contrivance of a twist traverse-net machine. He first studied the art of making the Buckingham or pillow-lace by hand, with the object of effecting the same motions by mechanical means.

It was a long and laborious task, requiring the exercise of great perseverance and ingenuity. His master, Elliot, described him at that time as inventive, patient, self-denying, and taciturn, undaunted by failures and mistakes, full of resources and expedients, and entertaining the most perfect confidence that his application of mechanical principles would eventually be crowned with success.