Like the Strutt family of South Normanton who began as farmers and small-time hosiers, and rose to take their place amongst the richest and most influential people in the land, Richard Arkwright rose from humble origins as a hard-up barber in Bolton to became the world's first great industrialist, and according to some contenpories the richest man in the country.

When Arkwright died at his Cromford mansion, Rock House, in 1792, he left a fortune estimated at £500,000 which in today's terms is more than £200 million.

Some have nothing but praise for the man who played a huge part in England's Industrial Revolution, and others point to his ruthless ambitious and rather cut-throat character as, essentially, a man who clawed his way to the top without much regard to others.

![]() For a further discussion on the pros and cons of this issue, please refer to my page about his origins and family scandals, and also this PDF book written in 1823 by Richard Guest that seeks to redress the balance and disprove the claims that Richard Arkwright was the inventor of the important new cotton-spinning machinery.

For a further discussion on the pros and cons of this issue, please refer to my page about his origins and family scandals, and also this PDF book written in 1823 by Richard Guest that seeks to redress the balance and disprove the claims that Richard Arkwright was the inventor of the important new cotton-spinning machinery.

Sir Richard Arkwright (23 December 1732 - 3 August 1792)

Inventor, Cotton Spinner and Entrepreneur

Sir Richard Arkwright is considered the father of the modern industrial factory system and his inventions were a catalyst for the Industrial Revolution. Rather than being an inventive genius, Richard Arkwright was a sharp-witted businessman who recognized the potential of other people's innovations, and made a very large personal fortune from developing them.

Family

Richard Arkwright was born in Preston, Lancashire, on 23 December 1732, the youngest son of Thomas Arkwright, a tailor of Preston. For a discussion on the family origins of Richard Arkwright please see this page mentioned earlier.

Money was tight for the Arkwrights when Richard was a youngster and schooling was out of the question. He was taught to read and write by his cousin Ellen. He was then apprenticed to a barber.

Chronology:

- 1732: Born in Preston, Lancs.

- 1748: Lewis Paul invented a machine for carding cotton which was to influence Arkwright.

- 1750: Moved to Churchgate in Bolton, Lancashire and worked as a barber in his own business.

- 1755 Married Patience Holt, Richard Jnr born the same year.

- 1761 Married to Margaret Biggens

- 1762: Started his own wig-making business, which involved him traveling the country to collect people's discarded hair. Opened his first tavern as a money spinner in Bolton. Met John Kay and obtained a spinning-machine idea from him and Thomas Highs of Leigh.

- 1767: Moved to Preston with John Kay, and joined forces with John Smalley and David Thornley; patented spinning frame.

- 1768: (April) Moved to Nottingham to avoid the machine-breakers in Lancashire. There he set up a small mill in Woolpack Lane.

- 1769: Approached Ichabod Wright, a banker from Nottingham, in search of funds to expand his business. He in turn introduced him to Jedediah Strutt of Derby and Samuel Need.

- 1771: Formed a partnership with Strutt and Need and set up a factory powered by water at Cromford in Derbyshire.

- 1775: Took out another Patent for modifications to his carding engine machinery. Cotton tarrif removed.

- 1779: Mill in Chorley, Lancashire destroyed by a mob of labourers.

- 1781: Prosecuted nine companies for breach of his patents. (April) Samuel Need died and Jedediah Strutt left. He went on to build factories in Manchester, other parts of Lancashire, Staffordshire and Scotland.

- 1783: Built Masson Mills at Matlock Bath, Derbyshire.

- 1785: Patents cancelled as it was proved in the Court of King's Bench that the intellectual property for many of the inventions lay not with him but with a selection of his partners, friends and rivals.

- 1786: Knighted by King George the Third.

- 1787: Became High Sheriff of Derbyshire

- 1792: Died at his home Rock House, Cromford

Barbering

Richard Arkwright received no formal education. He was apprenticed to a Mr. Nicholson, a barber at nearby Kirkham. He therefore began his  working life as a barber and wig-maker. In 1750 he moved to Bolton where he worked for Edward Pollit, a peruke maker. He soon set up his own barber shop in Deansgate, and

In 1762 Arkwright became the landlord of the Black Boy public house.

working life as a barber and wig-maker. In 1750 he moved to Bolton where he worked for Edward Pollit, a peruke maker. He soon set up his own barber shop in Deansgate, and

In 1762 Arkwright became the landlord of the Black Boy public house.

About this time he moved into a barber's shop in Churchgate and took on a skilled wig maker, John Dean, as his assistant. He was then able to spend part of his time travelling the country to buy women's hair to make into wigs. It was here that he got hold of and developed a waterproof dye for use on the in fashion 'periwinkles' (wigs) of the time, the income from which later facilitated his financing of prototype cotton machinery.

The barber shop in Churchgate, Bolton was demolished early in the last century. There is a small plaque above the door of the building that replaced it, recording Arkwright's occupancy.

Marriage

On 31 March 1755 he had married Patience, the daughter of Robert Holt, a school master. A son, also Richard, was christened on 19 December 1755. Patience died on 6 October 1756 and it was only after the death of his first wife that he became an entrepreneur.

His second marriage to Margaret Biggins on 24 March 1761 brought a small income that enabled him to expand his barber's business. He acquired a secret method for dyeing hair and travelled around the country purchasing human hair for use in the manufacture of wigs. During this time he was often in contact with weavers and spinners and when the fashion for wearing wigs declined, he looked to mechanical inventions in the field of textiles to make his fortune.

A daughter, Susanna, was born on 21 December 1761. They had three children, of whom only Susanna survived to adulthood.

First Inventions

By 1763, weaving had been greatly automated, since the invention of the Spinning Jenny by James Hargreaves, but spinning was still done by hand wheel. No method had been devised to spin cotton into a yarn that was strong enough to be used as warp threads. Consequently, calico was made, using linen for the warp and cotton for the weft. The cotton was carded and spun by women and then woven by men. Because it was a manually intensive process, there was often not enough cotton ready for when the weaver needed it.

Research into using mechanical rollers to replace hand spinning had started in the first half of the century; Lewis Paul had the first model in 1738, but further development was needed to make it profitable.

Seven miles down the road from Arkwright's home in Bolton is Leigh, where reedmaker Thomas Highs lived. Highs (1718-1803) originally produced a spinning-jenny that pre-dated, and was probably the prototype for, James Hargreaves's effort. Highs and his neighbour John Kay - a Clockmaker of Warrington - got together to design a machine that utilised draw rollers, in the style of Lewis Paul. But they had no investment funding.

Arkwright was always quick to spot a business opportunity. Desperate to keep Kay away from Highs, who was totally in the dark, Arkwright employed Kay the clockmaker and took him with him, first to Manchester, then Liverpool and on to Preston. In 1767, he engaged Kay's clockmaking skills in the construction of brass wheels (ostensibly for a "perpetual motion machine"). Six months later, after Kay had moved back to Warrington, Arkwright persuaded him to make a roller-based spinning-machine.

Kay, helped by two other local craftsmen, built a full-size version of what was to become the water frame, a machine with three sets of paired rollers that turned at different speeds. While these rollers produced yarn of the correct thickness, a set of spindles twisted the fibres firmly together. The machine was able to produce a thread that was far stronger than that made by the Spinning-Jenny produced by James Hargreaves.

This invention, which was different to the spinning jenny, because it used rollers, was capable of spinning many threads of different degrees of strength and thickness automatically. The only human intervention required was that someone had to feed the raw cotton into it and join the threads if they broke. The new Spinning Frame could produce stronger thread than the contemporary Spinning Jenny, but was far too large to be operated by hand.

(Following the patent trials of the 1780s, it was variously claimed that: Arkwright had envisaged the design before meeting Kay, that Kay had stolen High's ideas,or that Kay conceived the machine as well as building it. There is strong evidence to support the claim that it was Highs, and not Arkwright, who invented the spinning frame. However, Highs was unable to patent or develop the idea for lack of finance. Highs, who was also credited with inventing a Spinning Jenny several years before James Hargreaves produced his, probably got the idea for the spinning frame from the work of John Wyatt and Lewis Paul in the 1730s and 40s.)

After Kay's prototype convinced Arkwright of its feasibility, they moved to a secluded room in Preston, where Kay improved the technology through 1768, claiming to be developing a longitude machine. The secrecy and humming noises emanating from their experimental parlour led to accusations of witchcraft.

Though Arkwright was not rich, he had taken Kay to Preston as a "servant", with Kay giving his bond to serve Arkwright for twenty-one years and to keep their methods secret.

Relocation to Nottingham

In 1768, Arkwright built his first machine at Preston. He engaged the interest of two well-off relatives, John Smalley and David Thornley from Preston. Using their funding, he applied for a patent for his machine and took out a lease on premises in which to build and set up the machines. The leased property was converted into a mill, driven by horses turning a capstan. This was an inefficient form of power and before the mill was in production Arkwright and his partners decided to experiment with water power.

John Smalley, a forty-year old merchant and landlord of The Bull, was the second son of John Smalley of Blackburn, who in Feb 1750 in Preston had married Elizabeth Baxter. Elizabeth's mother Ellen was the widow of Arkwright's uncle Richard who died in 1727. (Ellen had married, after the death of uncle Richard, a Christopher Baxter.)

David Thornley, born 1741 had a father of the same name who had married in June 1738 Sarah Arkwright, the daughter of Richard Arkwright and Ellen.(This is the same Ellen above who was eventually Ellen Baxter.)

However, faced with serious opposition from the local spinning community, he and Kay moved to Nottingham in April, 1768, to avoid Lancashire machine-breakers. They set up a small mill in Woolpack Lane in the Hockley district, close to Hargreaves's jenny mill. It was horse-powered, but Arkwright began to realise that this could be only a stop-gap arrangement.

Arkwright patented the machine in 1769, without mentioning Kay, his "workman".

Arkwright patented the machine in 1769, without mentioning Kay, his "workman".

Patent Squabble Begins

James Hargreaves, who lived in Nottingham, learned about the patent and told John Kay. He responded by claiming it was HE (Kay) who was the machinery's true inventor. Arkwright then accused Kay of leaking its design to Hargreaves, and the two fell out; Kay accused Arkwright of stealing his work tools, and Arkwright filed a counter-charge. In the end, Kay fled Arkwright's Nottingham house (where he lived at the time) - permanently dissolving their relationship.

Ichabod Wright and Strutt & Need

Arkwright and John Smalley found their funds were dwindling and in 1769 Arkwright went to Ichabod Wright, a banker from Nottingham, in search of funds to expand the business. Wright introduced Arkwright to Samuel Need, a wealthy Nottingham hosier, and Jedediah Strutt, co-inventor of the Derby Rib stocking frame, for financial backing. They became co-partners in January 1770.

The newcomers financed the construction of the water-powered Cromford Mill on the River Derwent in Derbyshire, with Strutt and Need agreeing to take Arkwright's entire initial output of thread for their Nottingham stocking-knitting business.

Cromford was the start of a massive expansion of the cotton trade, and it was given a further boost in 1774 when Arkwright and his partners persuaded the Government to end the crippling import tariff on raw cotton, which had been imposed to protect the British woollen industry.

Cromford

Arkwright and his team had tried various experiments using horse-power, but the reliability and cheapness of water-power won the day. In 1771, the partners, Thornley excepted, decided to go to Cromford to build a water-powered spinning mill. Here there was a plentiful supply of water - Cromford Sough drained the Wirksworth lead mines and joined Bonsall Brook just above its confluence with the River Derwent. The sough had never been known to freeze so ensuring the water would not fail.

The site chosen for the mill lay west of Cromford Bridge by the Derwent. Nearby was a corn mill on Bonsall Brook and a short distance away near the bridge were smelting mills where lead ore was melted and formed into pigs (bricks) of lead. The land was leased from William and Mary Milnes for a yearly rent of £14, and the partners were given permission to divert Bonsall Brook and to construct mills, waterwheels, warehouses, workshops, smithies and anything else necessary for the working of the mills.

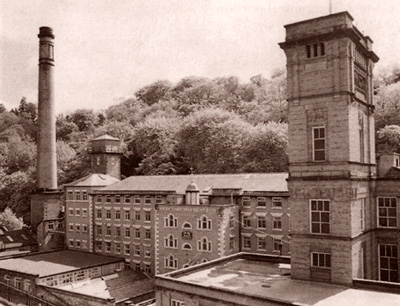

The first water-powered cotton spinning mill was speedily erected, and Arkwright's spinning machines soon came to be called Water Frames. The first Cromford mill was built in 1772 and a further mill at Lumford in Bakewell, was in operation by 1783

CROMFORD MILL IN 2008

CROMFORD MILL IN 2008

The first mill was built from the stone of Steeple Hall, Wirksworth, which Arkwright had bought from a Mr Greensmith, and demolished. The mill was 5 storeys high and the machinery was driven night and day. About 200 people worked there in 12 hour shifts, spinning at night and carding, combing etc in the day.

At Nottingham and at Crumford, near Matlock Bath in Derbyshire, there are mills that go by water and horses, that employ a number of industrious people in spinning of cotton yarn on a new principle, and in a very expeditious manner. That the yarn is of excellent quality, and peculiarly adapted to the making of warps for weaving; by which it is supposed the Manufacturers of cottons will be enabled to extend that branch of trade to many useful articles hitherto not made in England, such as muslins & cotton for printing in imitation of those called callicoes, ... Letter in Creswell's Nottingham Journal - January 2, 1773.

it soon became apparent that small town would not be able to provide enough workers for his mill. So he built a school so that his child workers could read and write, a chapel, and a large number of cottages near the mill to entice imported workers from outside the area.. Terraced three-storey buildings, constructed in 1776 for his workers, can still be seen in North Street.

Arkwright preferred weavers with large families. While the women and children worked in his spinning-factory, the weavers worked at home turning the yarn into cloth.

He also built the Greyhound public house (Greyhound Hotel) which still stands in Cromford market square. The hotel is planned to become a museum of Richard Arkwright.

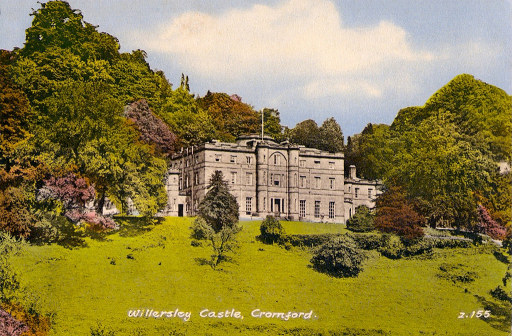

Sir Richard Arkwright transformed the small village of Cromford. In 1776 he purchased lands in Cromford, and in 1788 lands in Willersley, the vendor on both occasions being Peter Nightingale, the great-uncle of Florence Nightingale. As well as workers' housing he built a hotel, a new corn mill and established a market. Willersley Castle and St Mary's Church were started by him and finished after his death on 3 August 1792.

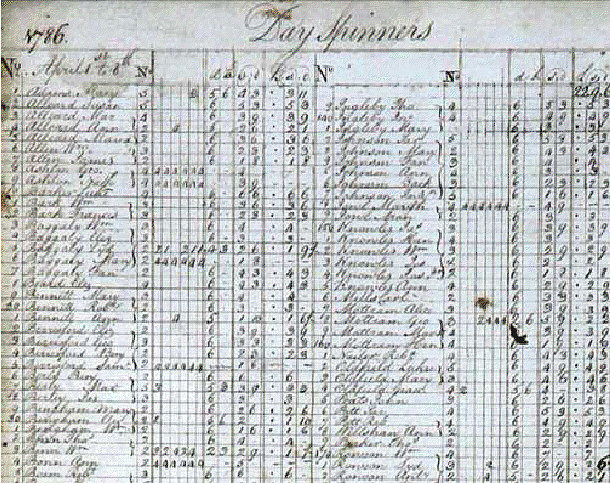

EXTRACT OF ARKWRIGHT'S WAGE BOOKS FROM LUMFORD MILL 1786-88

Richard Arkwright's employees worked from six in the morning to seven at night. Although some of the factory owners employed children as young as five, Arkwright's policy was to wait until they reached the age of six. Two-thirds of Arkwright's 1,900 workers were children. Like most factory owners, Arkwright was unwilling to employ people over the age of forty.

The wage books are some of the earliest surviving records for any of the Richard Arkwright Company mills, and demonstrate the differentiation between types of workers, reflected in a wide variation in rates of pay. The books cover the period 1786 to 1811, with significant gaps. It may be that some volumes remained at the mill after the sale in 1860, and were destroyed by the fire of 1868.

Ralph Mather described the work of the children in Richard Arkwright's factories in his book An Impartial Representation of the Case of the Poor Cotton Spinners in Lancashire (1780)

Arkwright's machines require so few hands, and those only children, with the assistance of an overlooker. A child can produce as much as would, and did upon an average, employ ten grown up persons. Jennies for spinning with one hundred or two hundred spindles, or more, going all at once, and requiring but one person to manage them. Within the space of ten years, from being a poor man worth £5, Richard Arkwright has purchased an estate of £20,000; while thousands of women, when they can get work, must make a long day to card, spin, and reel 5040 yards of cotton, and for this they have four-pence or five-pence and no more.

Expansion

By 1774 the firm employed 600 workers; in the next five years it expanded to new locations.

Arkwright now started to mechanise other parts of the process in order to keep pace with the spinning. On 16 December 1775 he took out a patent covering ten machines, including machines for carding and cleaning the cotton. The Cromford mill was a great success, and other cotton mills followed; Cressbrook in 1779, Bakewell in 1782, and Masson (Matlock) in 1783.

Cromford Mill was only the first in Arkwright's large and profitable empire of factories. which spread from Derbyshire into Staffordshire, Lancashire and up into Scotland. Masson Mill was built a short distance away from the Cromford factory and was the only mill powered by the river

In 1777 he leased the Haarlem Mill in Wirksworth, Derbyshire where he installed the first steam engine to be used in a cotton mill, though this was used to replenish the millpond that drove the mill's waterwheel, rather than to drive the machinery directly.

A large new mill at Birkacre, Lancashire, was destroyed in the anti-machinery riots in 1779. (see this link.)

In his factories he used the steam-engine that had recently been developed by James Watt and Matthew Boulton. When businessmen heard about Arkwright's success, they sent spies to find out what was going on in his factories. In exchange for money, some of Arkwright's employees were willing to explain how the factory was organised. Businessmen then used this information to build their own water-powered textile factories.

When Samuel Need died on 14th April, 1781. Arkwright and Jedediah Strutt decided to dissolve their partnership. Strutt was disturbed by Arkwright's plans to build mills in Manchester, Winkworth, Matlock Bath and Bakewell. Strutt believed that Arkwright was expanding too fast and without the support of Need, his long-time partner, he was unwilling to take the risk of further investments. He was also worried about the patent battles that were looming between Arkwright and men he claimed had pirated "his" inventions.

Masson Mill

In 1783 Arkwright created another factory, Masson Mill seen right.

The factory was made from red brick, which was expensive at the time. Masson Mill was the only mill to continue in production for any length of time, finally closing in 1991.

It is now the home of a designer discount outlet and textile museum.

Court Cases

From 1775, a series of court cases challenged Arkwright's patents as copies of others work, and they were revoked in 1785.

Arkwright in 1775 had obtained a grand patent covering many processes that he hoped would give him monopoly power over the fast-growing industry, but Lancashire opinion was bitterly hostile to exclusive patents.

In 1781, his right to this patent was challenged by other manufacturers on the grounds that the additional elements of the machinery were not his original idea. A lengthy court case ensued. Four years later, after seeing his patents restored temporarily, in another, definitive court battle, Thomas Highs, a remorseful John Kay, Kay's wife and the widow of James Hargreaves all testified that Arkwright had stolen their inventions. The court agreed: Arkwright's patents were finally laid aside.

Finally, in November 1785, Arkwright lost the argument and his patent was cancelled by the Court. This allowed other businesses to build their own versions of his inventions but still Arkwright was able to amass a vast fortune.

Nonetheless, In 1786 he was appointed by the King as the High Sheriff of Derbyshire. It was also in 1786 that he received his knighthood.

Post Mortem on Richard Arkwright

History has a habit of painting men as heros after the event. Many are the books and articles that present Sir Richard Arkwright as a beneficent clever inventor who transformed this country and launched the Industrial Revolution. The court cases are said to be the result of jealous rivals who envied Arkwright's business acumen.

Whatever he undoubtedly achieved - for which credit is due - Arkwright was not an inventive genius. He gladly used the inventions of others to build his empire. Indeed he stole the intellectual property of Thomas Highs and others to make his fortune, leaving Highs to die a poor man. (But then much the same could be said about Strutt and Woolatt who paid off the man who had the original concept of the Derby Rib and developed it into a viable machine, making their fortunes. This is little different to modern business practise such as the rip-off of Apple's original programming by Microsoft's Bill Gates. All is fair in love, war and big business!)

Arkwright's strength was in opportunism, spotting a good idea, and employing men with the talent to turn that idea into reality. He was more than happy to use the talents of other men as stepping stones for his ambition.

The Court of King's Bench said as much in 1785 when they rescinded his patents. The court heard evidence from Highs, Kay, Kay's wife, and James Hargreaves's widow, Elizabeth, among others. All testified that Arkwright had, in fact, stolen the inventions on which he had based his fortune.

Despite that, however, his work-force were fiercely loyal, and hundreds of armed men were on instant call to defend the mill against the threat from machine breakers. Arkwright kept a cannon loaded with grapeshot just inside the main factory gate, to emphasise the point. (see photo). The Derby Mercury wrote on 22nd October, 1779:

There is some fear of the mob coming to destroy the works at Cromford, but they are well prepared to receive them should they come here. All the gentlemen in this neighbourhood being determined to defend the works, which have been of such utility to this country. 5,000 or 6,000 men can be at any time assembled in less than an hour by signals agreed upon, who are determined to defend to the very last extremity, the works, by which many hundreds of their wives and children get a decent and comfortable livelihood.

Arkwright's lasting achievement, perhaps, was in doing for cotton what others had done for silk - and with the potential market for cheap cotton products so much bigger, his efforts at Cromford, elsewhere in Derbyshire, and in Lancashire and Scotland inevitably triggered that quantum leap in national productivity that became known as the Industrial Revolution.

Historians have pointed out that, although his machinery ideas were "borrowed," Arkwright did at least invent the factory system, the organisation and regimentation of labour in one specialised workplace giving the employer total control over the product and the means and cost of production.

But even this was not strictly true. Factories - particularly silk mills - had existed in England for more than 50 years before Arkwright opened his first big mill at Cromford in Derbyshire in 1771.

A testament to Arkwright's keen business sense came on his death in 1792, when it was found that he was worth half a million pounds, a staggering amount of money in the 18th century. In the twenty years to his death, in 1792, he had made sufficient fortune to have personally paid off the national debt!

He died in 1792 at his home of Rock House, Cromford on 3rd August 1792 and was initially buried at the church at Matlock. His remains were later moved to Saint Mary's Church at Cromford. Saint Mary's was a private chapel for Willersley Castle that was to have been his new Cromford residence.

Memorials

Sir Richard Arkwright lived at Rock House in Cromford, opposite his original mill. In 1788 he purchased an estate from Florence Nightingale’s father, William, for £20,000 and set about building Willersley Castle for himself and his family. However just as the building was completed it was destroyed by fire, and Arkwright was forced to wait a further two years whilst it was rebuilt. He died aged 59 in 1792, never having lived in the castle, which was only completed after his death. Willersley Castle is now a hotel owned by the Christian Guild company. (See below).

Following is an obituary for Richard Arkwright written a few days after his death.

The youngest of thirteen children, Sir Richard Arkwright was born in Preston on 23 December 1732. Arkwright will be remembered by most for his reformation of the way that people work. No one has had greater influence and indeed revolutionized industry than Sir Richard Arkwright. At 59 years of age, Arkwright died one of the richest men in England. It is estimated that his fortune amounted to something in the region of £500,000. In 1762 Arkwright started a wig-making business. This involved him traveling the country collecting people's discarded hair. While on his travels, Arkwright heard about the attempts being made to produce new machines for the textile industry. Arkwright also met John Kay, a clockmaker from Warrington, who had been busy for some time trying to produce a new spinning-machine with another man, Thomas Highs of Leigh. Kay and Highs had run out of money and had been forced to abandon the project. To Arkwright’s amazement, John Kay invited him to help produce this remarkable new machine. Arkwright accepted Kay’s offer and employed a local craftsman, and miraculously, it wasn’t long until the four actually produced the brand new “Spinning Frame”. Arkwright patented this and his “Water Frame” in 1769, which caused great rivalry between him and other cotton spinning entrepreneurs. In 1771 Arkwright invented the world’s first water powered cotton mill at Cressbrook in Derbyshire. A series of court cases followed as Arkwright attempted to prosecute rivals who had infringed his patents, culminating in an action brought by The Crown in 1785. Surely, Arkwright’s contribution to the cotton industry entitles him to be referred to the father of the industrial revolution and will always be remembered for his great, albeit stolen, inventions.

WEB LINKS

- Very full page about Arkwright and Cromford with photos

- The Arkwright Society at Cromford Mills

- Cotton Times about Arkwright and more

- Britain Unlimited page with photos

- Information Page (pdf)